It was the fall of 1994. I was 21 years old and living in Ypsilanti, Michigan—a loveable, dirty little college town populated, in equal parts, by students, dropouts, blue-collar workers, assorted eccentrics, and the truly insane.

It was the fall of 1994. I was 21 years old and living in Ypsilanti, Michigan—a loveable, dirty little college town populated, in equal parts, by students, dropouts, blue-collar workers, assorted eccentrics, and the truly insane.

I was coming off of four years in a college writing program that, for the moment, had done a great job of beating every last ounce of creative passion straight out of me. My girlfriend had just dumped me. I spent my nights loading semi trailers for UPS, and my days holed up in my bedroom with an already-outdated boom box and an alternate-tuned electric guitar, recording heartfelt but largely horrible song ideas for an imagined shoegazer band that never even came close to happening.

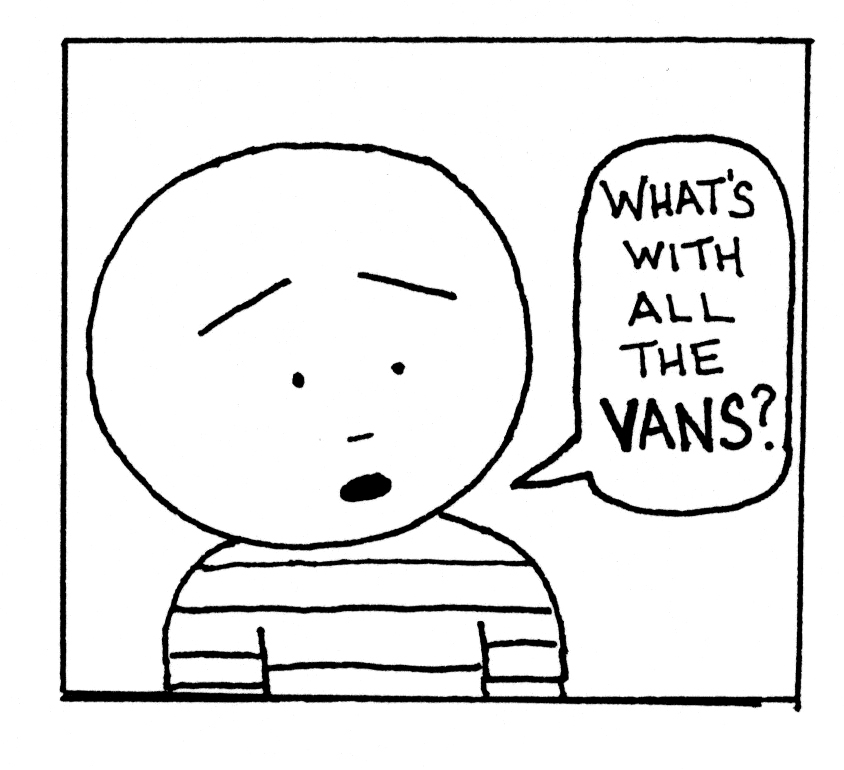

I was not, by anyone’s definition, on the fast track to success. And being 21, I was convinced that, unless I acted fast, my state of shiftless loserdom just might last forever. I needed to create something new and different and completely my own. And so I decided to make a ‘zine.

Its name was Stewie. And here it is, online for the first time, in its entirety.

How do I explain ‘zines to anyone born after 1990? They were blogs without the Internet. They were little books that we made ourselves, out of pen and paper and glue sticks and a whole lot of cover-up tape. We photocopied them, we assembled them, and then we gave them to other people—mostly in person, or by mail. Yes, mail. Strangers would send us handwritten letters, wrapped around dollar bills or little piles of stamps, and we would send these strangers our ‘zines, and they would write back to us—often long, emphatic letters about what life was like in their town (or country, or school, or prison). We traded stickers, and other ‘zines, and one-of-a-kind mix cassettes. It sounds ancient now—the way my grandparents spoke about life before television—but at the time, it felt mind-blowing, like discovering a secret, lawless club that stretched, clumsily, across entire continents.

For my subject matter, I finally took the advice of all those well-meaning professors: I wrote what I knew. And what I knew, at the time, was the world of music. In my immediate vicinity, it felt like every single person I knew was starting a band—or at least claimed to be.

Meanwhile, on the worldwide scale, a huge shift was underway: The weird, vibrant, varied underground music scene that, for years, we self-defined outsiders had all held so dear was busting wide open, and the massive entertainment corporations realized there was a lot of money to be made. Suddenly hair metal was out, replaced by the media-invented “grunge” and “alternative” rock—vague slippery genres that, in the eyes of me and my immediate peers, felt like one big watered-down ripoff of the real thing. (As I wrote in one particularly self-righteous song at the time, “The ignorant jocks all discovered punk rock, and the concerts were never the same.”)

Meanwhile, on the worldwide scale, a huge shift was underway: The weird, vibrant, varied underground music scene that, for years, we self-defined outsiders had all held so dear was busting wide open, and the massive entertainment corporations realized there was a lot of money to be made. Suddenly hair metal was out, replaced by the media-invented “grunge” and “alternative” rock—vague slippery genres that, in the eyes of me and my immediate peers, felt like one big watered-down ripoff of the real thing. (As I wrote in one particularly self-righteous song at the time, “The ignorant jocks all discovered punk rock, and the concerts were never the same.”)

The closest thing we’d had to a counterculture was being snatched up, dumbed down, and sold back to us as “Generation X”. Pre-ripped flannel shirts were being sold at Urban Outfitters for fifty bucks a pop. Once-scandalous rock songs were showing up in TV commercials—par for the course these days, but an unthinkable blasphemy at the time. Suddenly, it seemed, every magazine was publishing some variation of an article on this new, pessimistic generation of aimless slackers, and what it meant for the future of America. (Answer: the Internet. You’re welcome.) Everything was for sale, and we were still young and idealistic enough to be outraged by that. To paraphrase Walt Kelly: We had seen the product, and it was us.

Again, it’s a hard thing to explain now, in an era where nearly every type of media is instantly, equally accessible, and where an aspiring band’s biggest dream is to land an Apple commercial or an HBO theme song. I’ll spare you any further old-man rants on the subject and instead just refer you to the excellent book Our Band Could Be Your Life. (Which you probably won’t bother to read, or even click on, because your attention span is shot and you can’t be bothered to seek out anything that doesn’t wholly and instantly appear in magic-moron picture-vision at the first swipe of your Adderall-stained fingers across your life-sucking little touchscreen. Actually, who am I fucking kidding: Nobody except Mike White and maybe my mom are even going to read this far anyway. But I digress.)

I’d drawn cartoons as a kid, fueled by a heady mix of “Peanuts”, Mad magazine and (in an amazing feat of permissiveness and/or massive oversight by my parents) the autobiographical genius of National Lampoon-era Gahan Wilson. In my teenage years, the requisite superhero phase gave way to various lowbrow punk ‘zines—and in particular, the vicious anything-goes humor of local underground rags Motorbooty and Fun. In college, a chance encounter with Chester Brown’s Yummy Fur rekindled my interest in comic books—and their potential as something different and deviant—and Dan Clowes’ Eightball sealed the deal.

As for my actual drawing style (or lack thereof)… I’d slouched my way through a couple basic high school art classes, doing the bare minimum, and did my share of doodling in the notebook margins in college, but could never really draw. Or rather, had never bothered to really work at it. The decision, then, to suddenly create a full-fledged comic book—and not only that, but to release it into the world, publicly—was my equivalent of a garage-rock band: Put it out there, whatever way you can, and let your shortcomings dictate your style. At the time, I didn’t even know that specialty drawing pens existed—let alone ink, or brushes, or non-photo-blue pencils. (I was four issues in before I learned that professionals used guidelines for their lettering, and didn’t just naturally know how to write that straight.) My first issue was done entirely with a ball-point pen. And boy does it show.

The first run of Stewie #1 was 30 copies—photocopied at the Ypsilanti Kinko’s, and assembled and stapled by hand. (It would be the only batch I ever paid for; after that, various fans with sneaky access to Xerox machines would volunteer to copy it for free—the true unsung saints of the ‘zine age.) After the first issue, with its audience-participation contest and the offer of a lifetime subscription for the price of one dollar, I got a shit-ton of letters and printed more copies.

By Stewie #2, a month or two later, I had close to 50 subscribers. That number sounds ridiculous now, in this age of a million “likes”. But when you consider that, at the time, the distribution system consisted entirely of me handing out free copies around town, and that every one of those people who responded had to take the time to actually sit down, write a letter (almost always handwritten), stamp it, and mail it, it feels pretty damn impressive. At the time, it felt like the single most successful thing I’d ever done in my life.

After concluding the suspenseful three-part “Stewie’s Band” saga, I turned my sights to the straight-up autobiographical. Stewie #4: “Junior High Memories”, is, to this day, probably some of the funniest and (maybe not coincidentally) most honest writing I’ve ever done.

In the fall of 1995 I moved to San Francisco. By that point, Stewie had a couple hundred subscribers, and once I’d settled in to my new home, I felt obligated to keep the ‘zine going. But after the initial mad creative rush, I wasn’t sure I had any more great ideas—or at least none that directly related to my own, rapidly changing life.

My solution: Come up with the most far-out, ridiculous shit I could imagine. Hence Stewie #5: “The Custom Van Issue”, replete with its Space Buddha, UFO Bigfoot, and perhaps the greatest mural ever rendered in two-page black-and-white Xerox. I’m sure a few eyebrows went up with that issue (and for the record, no, I wasn’t on drugs when I wrote it.) Looking back at this particular piece of weirdness now, I’m proud of two things: First, I like to think that the artwork, in its own crazy lo-fi way, got a little bit tighter. (It was also, in a sign of the changing times, the first issue where I had access to a scanner and a computer—as evidenced by the fancy layout of the front and back covers.) Second, because of that issue, I met a badass custom-van-driving rocker named Beth Allen. Together we went on to found the website Don’t Come Knockin’ which, in its own crazy roundabout way, led to me to get a van and become a part of the real-life vanner scene. No Space Buddhas required.

My solution: Come up with the most far-out, ridiculous shit I could imagine. Hence Stewie #5: “The Custom Van Issue”, replete with its Space Buddha, UFO Bigfoot, and perhaps the greatest mural ever rendered in two-page black-and-white Xerox. I’m sure a few eyebrows went up with that issue (and for the record, no, I wasn’t on drugs when I wrote it.) Looking back at this particular piece of weirdness now, I’m proud of two things: First, I like to think that the artwork, in its own crazy lo-fi way, got a little bit tighter. (It was also, in a sign of the changing times, the first issue where I had access to a scanner and a computer—as evidenced by the fancy layout of the front and back covers.) Second, because of that issue, I met a badass custom-van-driving rocker named Beth Allen. Together we went on to found the website Don’t Come Knockin’ which, in its own crazy roundabout way, led to me to get a van and become a part of the real-life vanner scene. No Space Buddhas required.

So what happened? Why, after that crazy change in direction, did Stewie just end?

The long answer: In my real life, things were getting much more busy and interesting. I was couch-surfing for a while, playing in bands, traveling with other bands, partying (for better and for worse) with the original Burning Man crowd, and generally spending a lot of long nights exploring all the little treats that pre-tech-gazillionaire San Francisco had to offer.

The much shorter answer:

“Family Guy”. In particular, a snarky, suspiciously melon-headed baby named (all together now:) “Stewie”.

I’ll leave the grand conspiracy theories to others and just say that, when one finds one’s tiny homemade creation pitted against the most recognizable character on one of the most popular nationwide TV shows in existence, one gets real tired of saying, “No, not that one.”

In any case, two decades later, here it sits: the complete Stewie series. More artifact than art, at this point. Going back over these pages, it took all my willpower not to pull a George Lucas and just redraw the whole thing. But in the interest of authenticity, I left it mostly intact. The images that you see here were scanned from the original Xeroxed master sheets. Certain digital cleanups have been made, to remove obvious copier-induced toner spots or the crumbling remnants of ancient Liquid Paper. And, for obvious reasons, the pages are no longer arranged in digest booklet form. But otherwise, this is Stewie as it would have appeared in your hands, had you been lucky enough to find it 20 years ago.

Looking at it now, the “artwork” feels pretty painful to me, especially in the early issues. And there are one or two nasty epithets that, while never employed in a spirit of true hate, I probably wouldn’t include if I was drawing it today. But otherwise, I’m still pretty damn pleased with it.

Above all else, I hope this page serves as a fun bit of time-travel for that lucky few of you who got to read it the first time. And for the many more of you who are just joining us, I hope maybe you can find something to laugh at too.

All My Love,

Leon

December, 2014